COMMON GROUND

Laura Bivolaru

There is no doubt that humans

are visual beings. More than half of the human brain is involved in processing

visual information and, to no surprise, people would miss the sense of sight

the most if they were to lose one. Without vision, the flat surfaces of our

world would be meaningless – there would be no reading and writing as we know

them, no drawings in caves, and certainly no photographs. But it’s also worth

keeping in mind that vision is a cultural product and Western Europe is

particularly indebted to (and possibly entrapped by) the scientists and artists

of the Renaissance, who understood the eye as a camera obscura and invented

linear perspective. Until Impressionism, the cognisant self remained an

extension of the one eye that perceived the world.

![]()

Today we understand the self as a more porous, even soft entity, that constantly negotiates the relationship with its environment through all the senses and with the help of a myriad of ideas that diverge from the image of the Man of Reason. It is in this context that Antonia Attwood and Georgia Clemson have put together Common Ground, an exhibition at ArtLacuna in London that seeks to represent the invisible emotional world. Their works are rooted in photography, a medium historically connected to the desire of capturing life precisely as it unfolds before the eyes; however, by intervening in the source code of the images and by pushing the analogue process beyond its photographic indexicality, they imaginatively explore the fluctuating, permeable boundary between the privacy of the self and the open space in which it moves and encounters others.

Attwood’s images are originally holiday photographs, taken while on vacation in Japan in 2017 with her then partner. Following their relationship’s end, she revisits these digital photographs and introduces in their code fragments of diary entries from the time of the separation. As viewers, we cannot access her writing, instead what is shown to us is how these reflections have corrupted the images. They are joined on the wall by a print of Japan’s rail network in reverse, which has a strange three-dimensionality, and a screening of short videos from the same time taken at the Tokyo Sea Life Park. Their code has been altered as well, rendering the aquatic life forms in vivid, surreal colours, which echo both the corruption lines in her black-and-white images and Clemson’s multicoloured works.

![]()

![]()

What was once a holiday now becomes a journey, as Attwood processes her own feelings by moving backwards and forwards in time, between memories, a hurtful present and the hope of a painless, balanced future. The photographs establish a clear boundary between public and private, allowing us to only imagine her self’s estrangement and subsequent healing and to project our own experiences onto them. We’re left wondering about the network of associations that these images are part of now - can they still recount happy times or are they forever scarred? Could they do both at the same time perhaps? Attwood’s works ultimately hint at the unstoppable flux of our inner worlds, which we constantly reconfigure in a constellation of thoughts and emotions with various degrees of awareness. We may want our representations of them to be as neat as a transport guide, but the truth is that we are all islands that host the energy of tumultuous metropolises.

![]()

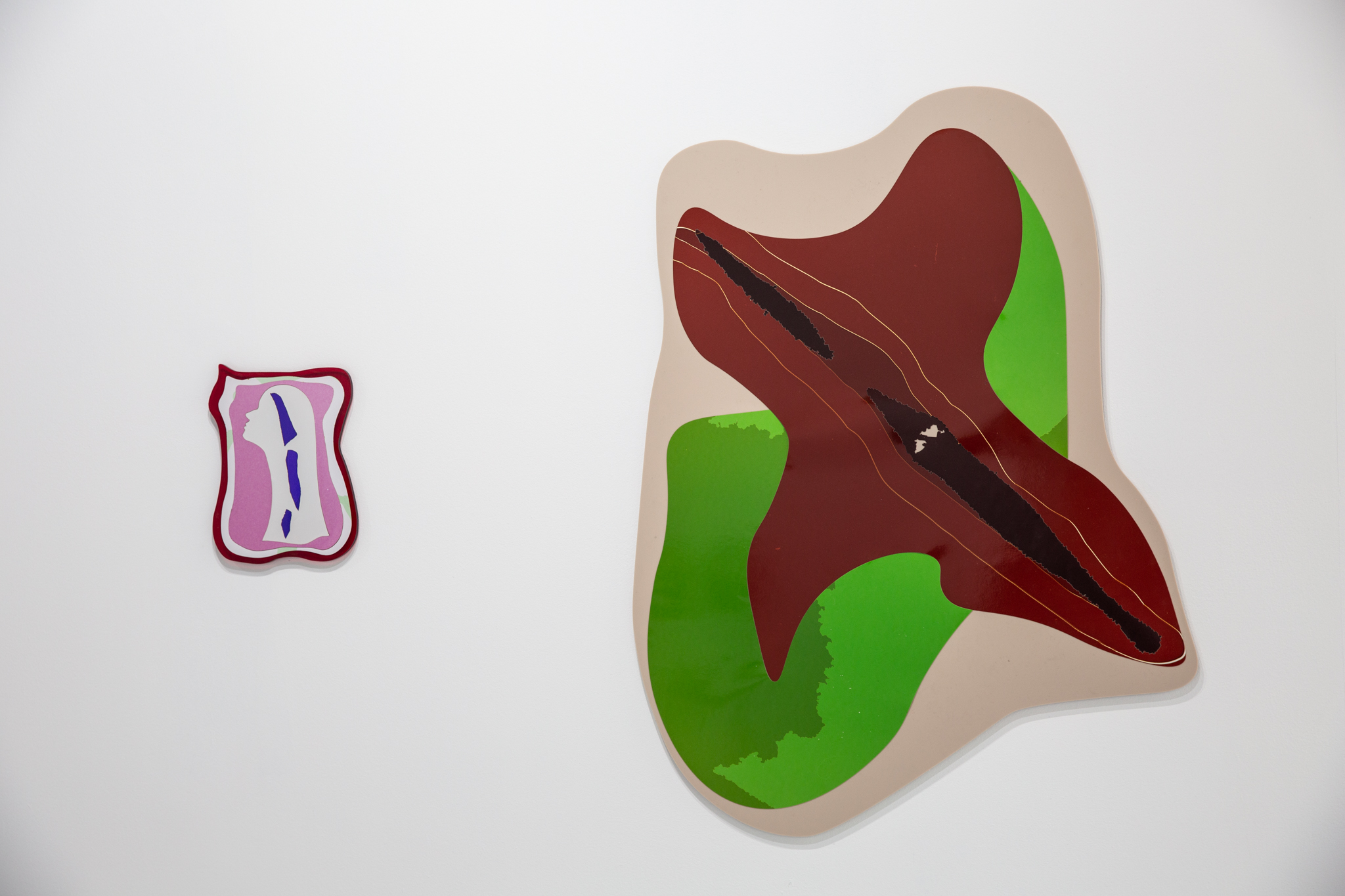

The metaphor of the self as an island reverberates in Clemson’s work, a series of objects displayed both on the wall and on the floor, that, although flat, share the multidimensionality of Attwood’s graphic map. Beginning by drawing bodies in various positions, the artist isolates the negative space in-between touching body parts, then creates photograms based on these shapes that defy the fixed rectangularity of the pictorial frame. These are photographic objects, or even sculptures, that with their sinuous shapes and organic colours recall the layering of landforms and natural features, together constituting an archipelago of the Other. To guide the viewers further, Clemson also created six spoken word tracks that follow an imaginary explorer’s quest to the land of ‘Another’. Titled after body parts, such as The Fingertip, The Heel, or The Innards, all under the umbrella of The Crook of the Elbow, the oral short story, voiced by artist Victoria Louise Doyle, tests the boundaries and rules of this newfound place, which eventually drives the foreign explorer away.

![]()

The Other is here imagined as an autonomous territory, a nation whose environment one needs to adapt to, as well as adhere to its idiosyncratic laws in order to fully know it and to cohabit. This idea resonates with feminist scholar Sara Ahmed’s argument in The Cultural Politics of Emotion that emotions shape collective bodies just as much as individuals; whoever does not align with the group’s emotions becomes an outsider to the community. Imagining the self as a nation and a collective as an individual is a powerful game that raises many questions about our being in the world - are we respectful guests on Another’s land or are we entitled conquerors? Can we truly know each other and not have our boundaries challenged? How can we establish painless relationships between ourselves?

Clemson’s inner microcosms and Attwood’s therapeutic process illustrate contemporary photography’s potential to represent and imagine the self with a playful visual language that draws from current concerns in psychology and sociology. In its intention a nod to Symbolist photographers, who sought to represent states of mind and the links between matter and spirit, Common Ground asks what happens when we visualise the unrepresentable - does seeing open us up to new forms of knowing?

Common Ground was open at ArtLacuna, London in May 2022.

Listen to The Crook of the Elbow and other islands

Read the exhibition publication

Georgia Clemson

Antonia Attwood

Victoria Louise Doyle

Today we understand the self as a more porous, even soft entity, that constantly negotiates the relationship with its environment through all the senses and with the help of a myriad of ideas that diverge from the image of the Man of Reason. It is in this context that Antonia Attwood and Georgia Clemson have put together Common Ground, an exhibition at ArtLacuna in London that seeks to represent the invisible emotional world. Their works are rooted in photography, a medium historically connected to the desire of capturing life precisely as it unfolds before the eyes; however, by intervening in the source code of the images and by pushing the analogue process beyond its photographic indexicality, they imaginatively explore the fluctuating, permeable boundary between the privacy of the self and the open space in which it moves and encounters others.

Attwood’s images are originally holiday photographs, taken while on vacation in Japan in 2017 with her then partner. Following their relationship’s end, she revisits these digital photographs and introduces in their code fragments of diary entries from the time of the separation. As viewers, we cannot access her writing, instead what is shown to us is how these reflections have corrupted the images. They are joined on the wall by a print of Japan’s rail network in reverse, which has a strange three-dimensionality, and a screening of short videos from the same time taken at the Tokyo Sea Life Park. Their code has been altered as well, rendering the aquatic life forms in vivid, surreal colours, which echo both the corruption lines in her black-and-white images and Clemson’s multicoloured works.

What was once a holiday now becomes a journey, as Attwood processes her own feelings by moving backwards and forwards in time, between memories, a hurtful present and the hope of a painless, balanced future. The photographs establish a clear boundary between public and private, allowing us to only imagine her self’s estrangement and subsequent healing and to project our own experiences onto them. We’re left wondering about the network of associations that these images are part of now - can they still recount happy times or are they forever scarred? Could they do both at the same time perhaps? Attwood’s works ultimately hint at the unstoppable flux of our inner worlds, which we constantly reconfigure in a constellation of thoughts and emotions with various degrees of awareness. We may want our representations of them to be as neat as a transport guide, but the truth is that we are all islands that host the energy of tumultuous metropolises.

The metaphor of the self as an island reverberates in Clemson’s work, a series of objects displayed both on the wall and on the floor, that, although flat, share the multidimensionality of Attwood’s graphic map. Beginning by drawing bodies in various positions, the artist isolates the negative space in-between touching body parts, then creates photograms based on these shapes that defy the fixed rectangularity of the pictorial frame. These are photographic objects, or even sculptures, that with their sinuous shapes and organic colours recall the layering of landforms and natural features, together constituting an archipelago of the Other. To guide the viewers further, Clemson also created six spoken word tracks that follow an imaginary explorer’s quest to the land of ‘Another’. Titled after body parts, such as The Fingertip, The Heel, or The Innards, all under the umbrella of The Crook of the Elbow, the oral short story, voiced by artist Victoria Louise Doyle, tests the boundaries and rules of this newfound place, which eventually drives the foreign explorer away.

The Other is here imagined as an autonomous territory, a nation whose environment one needs to adapt to, as well as adhere to its idiosyncratic laws in order to fully know it and to cohabit. This idea resonates with feminist scholar Sara Ahmed’s argument in The Cultural Politics of Emotion that emotions shape collective bodies just as much as individuals; whoever does not align with the group’s emotions becomes an outsider to the community. Imagining the self as a nation and a collective as an individual is a powerful game that raises many questions about our being in the world - are we respectful guests on Another’s land or are we entitled conquerors? Can we truly know each other and not have our boundaries challenged? How can we establish painless relationships between ourselves?

Clemson’s inner microcosms and Attwood’s therapeutic process illustrate contemporary photography’s potential to represent and imagine the self with a playful visual language that draws from current concerns in psychology and sociology. In its intention a nod to Symbolist photographers, who sought to represent states of mind and the links between matter and spirit, Common Ground asks what happens when we visualise the unrepresentable - does seeing open us up to new forms of knowing?

Common Ground was open at ArtLacuna, London in May 2022.

Listen to The Crook of the Elbow and other islands

Read the exhibition publication

Georgia Clemson

Antonia Attwood

Victoria Louise Doyle