Hang Ten

Laura Bivolaru x Tom Medwell with Ning Zhou, Gülce Tulçalı and Yushi Li

One roll of film, ten photographers, and an exhibition at ArtLacuna, London, in May 2021. Artists: Marie Smith, Ning Zhou, Tris Bucaro, Gülce Tulçalı, Gökhan Tanrıöver, Yushi Li, Tom Medwell, Eleonora Agostini, Ramona Güntert, David Barreiro.

L: How did you come up with the concept for the exhibition?

T: The initial idea was very simple. There is a game called Consequences, or Exquisite Corpse, invented by André Breton, where people take turns to write a line and then fold the paper before passing it to the next person, and I wondered how this might be possible with a camera. Medium format film lends itself quite well to this - with 6x7 negatives you get ten shots on a roll, a good number for a small show. But then I realised that the production of this roll could also function as a work of art - both as the performance of creation, and also as a testament to the wildly diverse possibilities of the medium. It was also not long after graduation, a moment which I’m sure is familiar to many, when the opportunities and exhibitions seem to be getting hoovered up by quite a small group of fellow graduates, based more on their ability for self-promotion than the work they produce, and so there was also a feeling of trying to bypass the problematic gatekeepers of the artworld and to make something happen all by myself. I’d never put on any sort of exhibition before and I wanted to see if I could make it as easy and with as little drama for the artists as possible. There was also a sort of joy for me in seeing how artists I greatly admire create their work, as well as a slightly malicious glee in putting them on the spot with just one shot.

L: Has the lockdown played any role in coming up with this ‘safe collaboration’ idea?

T: Certainly, although it was perhaps also that the idea seemed more feasible in lockdown than other ideas I have had. In part that was to do with taking full responsibility for production on myself; it meant that I was the only point of contact anyone involved in the project needed, and so we could work collaboratively in a safe and separate way. Shooting began with a very distanced handover of the camera outside The Photographers’ Gallery, and continued in whatever way the people shooting were comfortable with. Circumstances were changing rapidly, and there were several postponements and technical issues to overcome, but also I think many people involved in the show were excited to have something productive to do. For me, it gave me a bit of purpose at a point when the world seemed listless and in a permanent state of waiting.

![]()

T: The initial idea was very simple. There is a game called Consequences, or Exquisite Corpse, invented by André Breton, where people take turns to write a line and then fold the paper before passing it to the next person, and I wondered how this might be possible with a camera. Medium format film lends itself quite well to this - with 6x7 negatives you get ten shots on a roll, a good number for a small show. But then I realised that the production of this roll could also function as a work of art - both as the performance of creation, and also as a testament to the wildly diverse possibilities of the medium. It was also not long after graduation, a moment which I’m sure is familiar to many, when the opportunities and exhibitions seem to be getting hoovered up by quite a small group of fellow graduates, based more on their ability for self-promotion than the work they produce, and so there was also a feeling of trying to bypass the problematic gatekeepers of the artworld and to make something happen all by myself. I’d never put on any sort of exhibition before and I wanted to see if I could make it as easy and with as little drama for the artists as possible. There was also a sort of joy for me in seeing how artists I greatly admire create their work, as well as a slightly malicious glee in putting them on the spot with just one shot.

L: Has the lockdown played any role in coming up with this ‘safe collaboration’ idea?

T: Certainly, although it was perhaps also that the idea seemed more feasible in lockdown than other ideas I have had. In part that was to do with taking full responsibility for production on myself; it meant that I was the only point of contact anyone involved in the project needed, and so we could work collaboratively in a safe and separate way. Shooting began with a very distanced handover of the camera outside The Photographers’ Gallery, and continued in whatever way the people shooting were comfortable with. Circumstances were changing rapidly, and there were several postponements and technical issues to overcome, but also I think many people involved in the show were excited to have something productive to do. For me, it gave me a bit of purpose at a point when the world seemed listless and in a permanent state of waiting.

L: Tell me more about the process of shooting the roll of film. How did you pick the artists? How did you choose the order in which they took their photograph? Did you give them any instructions?

T: When it occurred to me that the project overall would function well as an exhibition of the possibilities of the negative, the picking process became quite simple. The first few people I reached out to were artists I know quite well and had wanted to exhibit with, and then I began approaching people with as varied practises as I could reasonably find. Of course I also had in mind that I wanted people who would say yes, and I asked a couple of people for recommendations. The main thing was that I wanted all the work to be as different as possible.

The order was somewhat dictated by availability; it was a very happy coincidence that when we hung the work in the gallery it seemed to have a perfect rhythm to the sequence, particularly the more installation-based work. I asked them as a group about what film they’d be happy with, and we settled on Ilford Delta 400 as a good quality all-round film, and then I loaded it in my camera and delivered it to them. Some needed the camera for a few days, others shot while I waited. It was a bit nerve-wracking letting it out of sight, particularly once several people had shot, as any mistake had the potential to ruin a lot of work, but it was a pleasant anxiety in a way - the feeling of getting something done after months of being locked indoors.

L: Was each artist responsible for the print in the exhibition too?

T: I gave everyone involved the option of doing whatever they wanted with the negative, printing or scanning and printing themselves, or asking myself or one of the others to print for them. A big part of the concept was to show the development of the negative on the film into something else on the wall, so there was no brief or dictation beyond asking them to consider the availability of the amount of space we’d likely use. Many of the artists have a strong darkroom practice, and it was interesting to see how they work with a negative to produce an image. One allowance I decided on due to lockdown was eventually cutting the negative to let everyone make their own prints; originally I’d wanted to keep the strip entirely intact and hang it in the middle of the space, but the logistics of this in lockdown were prohibitive, and so we settled on a print of a scan of the whole strip, which worked quite nicely in the end.

L: Who owns the film? How did you go about the ownership of the photographs?

T: While I consider the concept and execution of the project to be my own work, the prints and negatives were always the property of the artists involved.

L: How far has the film travelled?

T: I don’t think it has left London.. but I’m not sure. It certainly did a lot of sightseeing.

L: Were the artists aware of the images before and after theirs? Do you think a sense of narrative emerged or is this rather a collection of single images representative for each artist’s practice?

T: For the most part I think the artists were unaware. A couple of them lived together and worked with each other to produce their work, and I also helped out occasionally (David covered my hand in paint for his piece). I’m not sure about narrative; I think a few of the artists used it as an opportunity to experiment publicly, as with Eleonora, and perhaps that experimental approach is part of what ties the all work together as a series.

L: Working in the darkroom can often be solitary. What was the balance between collaboration and individual work?

T: I think the balance came from conversation; it felt like a time of gradual opening up and unfolding from hibernation, and a sort of tenderness after the trauma of the year, a shared fragility, but also hope. Also ego: I don’t think anyone wanted to be the one who made a mistake, or the one whose work looked bad next to the rest, almost a sort of competitiveness, but that is a sort of collaboration itself.

L: The approaches were very diverse. What are some of the themes the artists explored?

T: There’s huge diversity in the artists’ interests as well as their approach to producing the work in the show. Marie’s piece is a bit about the unseen history of a place - a photograph of where a river runs underground, now built over and invisible. Ramona makes work which seems to me to almost be artefacts from a different world; there’s a transformational quality to her piece, strange organic shapes which almost slide off the print and make me question where the image begins and ends. My piece is a time-sculpture recreation of van Gogh’s grave, built around a cutting of ivy taken from his grave. Every work in the show has a grand story to it.

photo: Ning Zhou

N: For me, the most challenging thing is that I only have one chance to do my shot, because usually I make a lot of mistakes in shooting films. I am worried about whether the exposure is accurate and whether it is in focus. It was fun but, yes, stressful!

G: The most challenging aspect of taking one photograph is not to be able to play around as I would normally with a roll of film. For me, having a roll unshot is like having an empty canvas, which is sort of a playground. So the hardest part was not to be able to play around with variations, objects, subjects around me or of my mind, this is one of the reasons why I made a rather "mock-upy" photo.

Y: I think the most challenging part is to make sure everything works, as there is only one chance to take the photograph. I remember that there was something wrong with the flash sync during my shoot, so I was not sure what I captured on the film. I guess this is also what is both difficult, but also exciting about working with analogue.

L: How did you approach the concept? Did you find it liberating or restrictive?

N: I really love the concept of Hang Ten. Ten photographers each took one photo on the same roll film. I will say the content of the photo is liberating, because basically we can shoot whatever we want. Regarding the restrictive aspects of this project, I think it is not only in terms of quantity. From the perspective of the overallity of the group exhibition, I think Tom definitely wants to see diversity. I did spend some time conceiving the photo.

G: I honestly found it liberating. I am not sure if it can be done all the time, but I do think this was one of the cases where restriction and creativity had a good balance. I guess unless it is censorship sometimes restrictions do trigger what can be done with "now".

Y: I think it is quite interesting to have 10 photographers shooting on the same roll of a film, giving each photographer only one shot. With the development of digital cameras and smart phones, I think we sometimes take too many pictures nowadays. So it’s good to only have one chance sometimes, which makes the image more special.

photo: Gülce Tulçalı

L: How does your photograph fit into your wider practice?

N: Most of my works are black and white self-portraits. The photo I took for Hang Ten was also a self-portrait. This photo was in line with my diary project, "Questions I Ask Myself During Lockdown", I was working on at the time. I photographed my partner and I on black and white film in both projects.

G: The photograph is meant to be a part of series where a conversation between the veil and five senses, it is kind of a funny image of imagine if the veil was showing off the mouth but not the eyes.

Y: In my practice, I have been trying to play with the power dynamic inherent in the gendered gaze through projecting my fantasies onto different male bodies. I think it’s interesting to explore the male representations in different ways. I did this photograph more like an experiment for a new project I am doing at the moment, which is a series of photographs of abstract close ups of the male body.

L: Ning, only you and Eleonora chose to take portraits. Has the idea of collaboration played an important role in shooting your image?

N: Yes, definitely! I will share the story behind my picture here: One morning, my partner woke up and told me about her dream. She dreamt about going to a camera shop together because my dad wanted to buy me a graduation gift. There were many interesting cameras and lenses in that shop, all were over 10K. She said in her dream I didn’t buy any gears, but I chose to buy a 80p Polaroid photo instead. And in that photo, it was us hugging. She said she was so touched. So when Tom told me about Hang Ten, I thought I could take this photo in her dream and touch her again. (So romantic). So I asked her to draw this picture and we took this photo one day while Tom was waiting on the sofa. In the end, she said this picture was not the one she dreamt about. Haha.

L: Gülce, your image and its curation conveyed a particular sense of sensual uneasiness. The tongue, seemingly disconnected from its housing body, reaches out of the photograph. Other photographs embody narratives, but yours is a strongly symbolic image that encourages a visceral reaction. How do you approach working with symbols?

G: I am really happy to hear this comment from you actually, most of the work I do is very instinctive. Usually an image appears in my head and I have to get it, the meaning/research/reference often comes through later, if I am not looking for a missing piece in the body of work. Sometimes those images are problematic or worthless when critical thinking is involved. For this photograph, I did have the thought behind the tension and the veil for a time, but the image itself came through the minute I assigned the photograph a time to be taken, when it was my turn with the roll. I love/hate working with symbols. First, symbols are problematically totalising when they appear in photography, they are less dense, they flow better in moving image, where there is more room for them to breathe and co-exist with other explanatory materials. And because I approach image-making often metaphorically, sometimes working with symbols in a photograph makes the photograph way too charged for the narrative. I still find them essential to visualise authority - women dynamics, but my understanding/experiments of them is ever-changing.

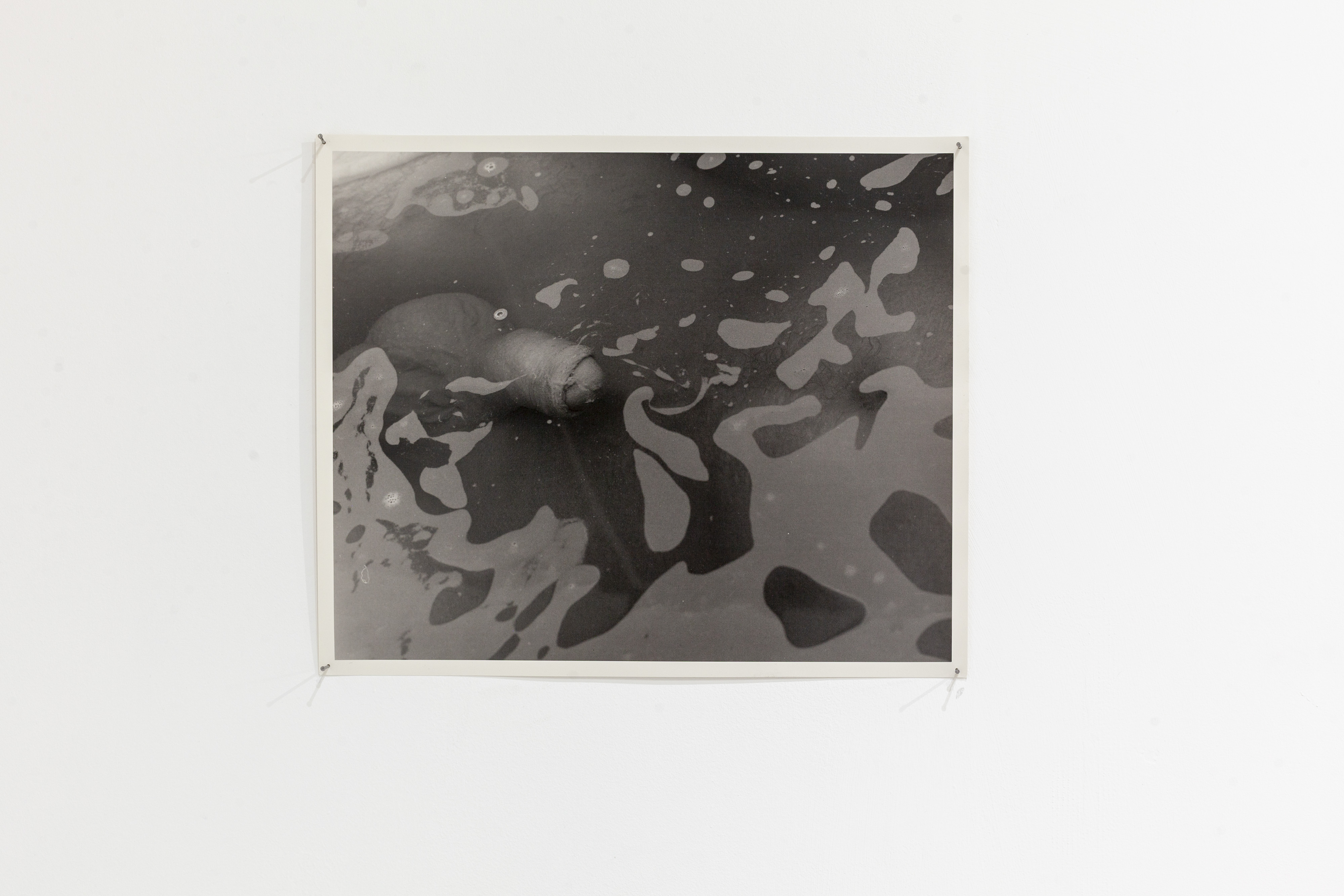

L: Yushi, your image plays with layers, with the relationship between transparency and opacity. A photograph is always a narrow framing of the world and, as viewers, we are more or less aware that we are shown something, but we are also missing out on other things. Here, however, the body is deliberately obscured. How do you think the viewer can benefit from this awareness that something is being kept from them?

4. In my opinion, I think an image that does not reveal everything is more interesting, as it allows the viewer to have room to imagine and desire. Apart from that, this photograph is kind of inspired by Lacan’s idea of the phallus, which is the signifier of desire and has to stay veiled. In my photograph, I use the water as the veil to hide the phallus, behind which is not just the penis, but also whatever the viewer desires.

photo: Yushi Li

Tom Medwell Website | Tom Medwell InstagramNing Zhou Website | Ning Zhou Instagram

Gülce Tulçalı Website | Gülce Tulçalı Instagram

Yushi Li Website | Yushi Li Instagram