INSULAR TIME

Cinematic duration and the enduring selfLaura Bivolaru

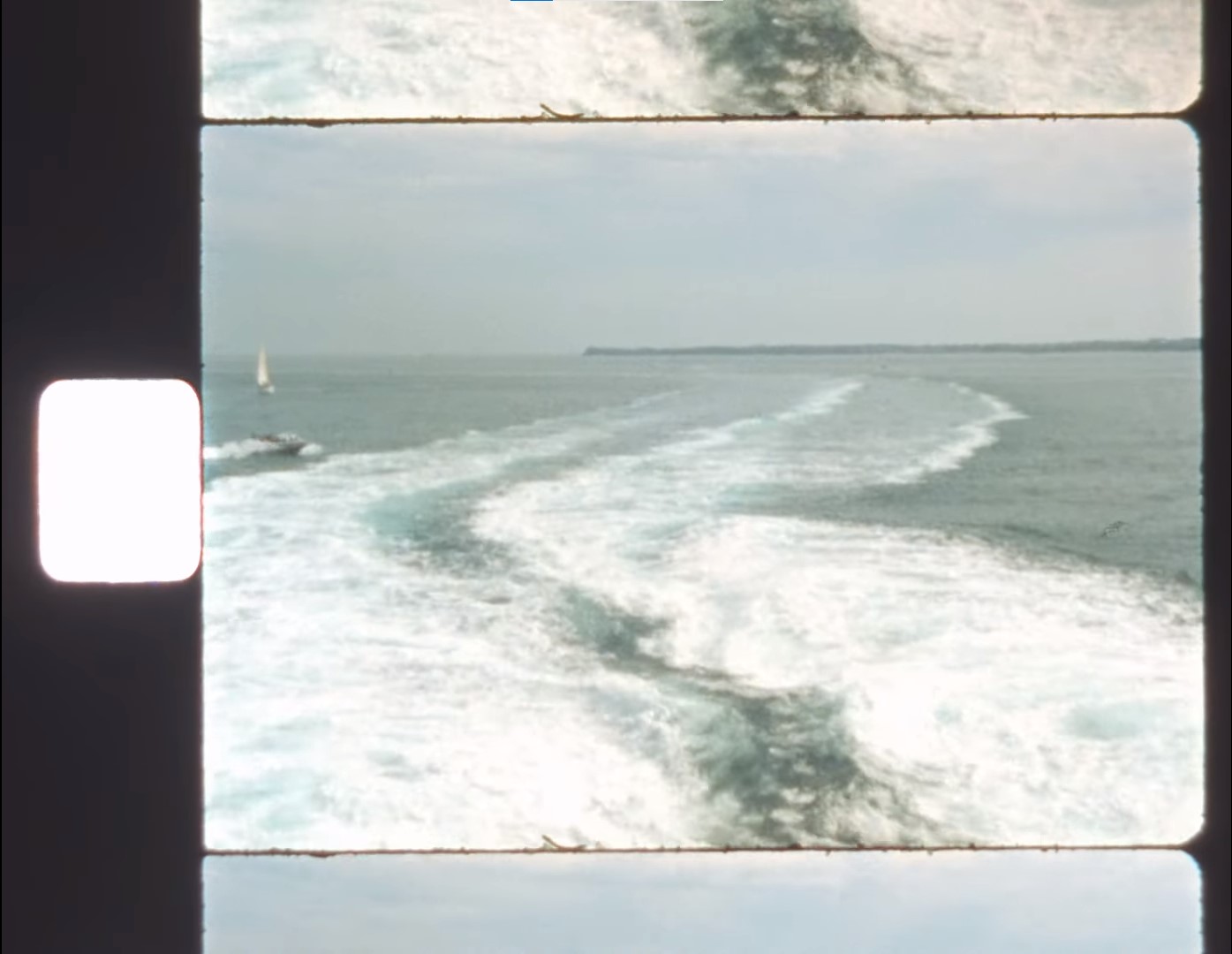

The boat leaves a foamy trail behind it as it arrives one morning to the Island. Some come here to forget about the rest of the world, while for others this land is their whole world – fertile soil inhaling salty air, exhaling sweet water. Some visit and others never float away, some take the Island’s likeness, while others only hold it in their memories. In the meantime, water moves around the Island, inside the earth, across the sky.

Even after satellites mapped the entire surface of the earth and didn’t leave any land to be discovered, islands have remained in the collective imagination somewhere in between the real and the virtual, where, at once, anything could happen and nothing ever happens. Home to fantastic creatures and lost civilisations or devoid of human life, hiding treasures or advanced technology, destination for love-seekers, holiday-makers, inmates, and exiled emperors, islands are portals, places of possibility where imagination can conjure up a parallel time.

In Alexander Mourant’s Super 8mm short film, A Vertigo Like Self, we appear to travel to such a place on a summer day. The light changes its temperature from milky bright in the beginning to incandescent in the middle and to golden towards the end, creating a narrative time frame of one day, from morning to evening. Life here flows at a mellow pace, echoing nature’s rhythm. In between the crops growing without much human attention, the quiet cloister, and the untouched lush forest, there is a glimpse of urban pulsations and serpent roads. As the morning turns into afternoon and the camera travels deeper into the landscape, all human activity is left behind. Before the end of the day, when the camera returns to the shore and departs on a boat, it records a woman, high up in the mountains, sitting contemplatively during the magic hour and taking in the view.

These two movements, through time and space, comprise the structure of the film, creating a coherent narrative of a journey from the flatness of the shore and agricultural plains to the elevation of waterfalls and mountains. There is also an element of circularity provided by the two symmetrical events of coming and leaving on the same route, by sea. As opposed to a linear, progressive narrative, here the purpose of the journey seems to be to ascend to the solid pinnacle, then return to the flux of the waves.

![]()

However, the image of water haunts the entirety of the journey on land – sprinkles that irrigate the crops, a fountain, a waterfall, a waving body of turquoise water. This liquid flow impregnates the rhythm of the film, so much that any other movement seems to resemble it – the shimmer of ribbons covering the town square, a young man drawing in the cloister, the trembling of leaves, the road being left behind in a car’s mirror. This sense of instability halts towards the end, with the images of cliffs and of the woman. She is first seen in contre-jour, then a close-up on her hand follows, after which she is shown with her back towards the camera. The blue of her blazer and of her nail polish stands out as a marine reference. She never moves, but her fist clenching the chair’s arm betrays a sense of uneasiness. On the wrist, a watch shows the time - 6:20. Her stillness is in such stark opposition to the rest of the subjects, that this encounter seems a climactic point, turning her into an oracular figure. Her statuesque stance appears to resist time and perhaps the young man previously seen drawing an architectural study has come to learn about keeping time, about pausing it, or the futility of such an attempt.

Cinematic time is what Mourant seems keen to explore in his short film. Firstly, there is no clear narrative or defined characters – the camera records what lies in front of it. There is no sound, either. It is, of course, by the power of the cut and of montage (in-camera, in this case) that any sense of a storyline becomes possible. Cinema is, after all, a sequence of photographic stills, while any story belongs to the viewer only. Mourant’s interest in the relationship between still and moving image is made apparent by the choice to include the entire surface of the film in the projection, as well as parts from the neighbouring frames. This entails that while viewing the film, at any given moment, the main frame shown is bordered by its predecessor in time to the top and by its successor to the bottom, being only separated by a fine, black line.

This representation of the flow of time may be indebted to late 19th century phenomenological analysis. Edmund Husserl, in his On the Phenomenology of the Consciousness of Internal Time (a collection of essays written between 1893-1917), argues that we don’t experience time in separate units, but consciousness continuously connects moments into a flow, by retaining what has just passed and anticipating what is coming. Temporality is therefore immanent, a product of the self. The same applies to cinematic representation – although made up by units, it is the self that experiences it as temporal. However, after more than a century of standardised, capitalist time, is the self still perceiving duration in the same way?

It might be useful to see what clock-ruled life looked like at its beginning. In The Painter of Modern Life (1863), Charles Baudelaire writes about the modern artist-flâneur:

‘For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite. (...) Or we might liken him to a mirror as vast as the crowd itself; or to a kaleidoscope gifted with consciousness, responding to each one of its movements and reproducing the multiplicity of life and the flickering grace of all the elements of life.’

![]()

Perhaps we have inherited from modernism a kaleidoscope-like consciousness or we have adapted to modern life by acquiring it as a defence mechanism. The movement of the city, of people, merchandise, and even of nature and the cosmos turned from cyclical to progressive. However, not everybody responded to this cultural shift as enthusiastically as Baudelaire.

In his Illuminations (1955) commentary on the poet, Walter Benjamin writes that the emotions aroused by modernity in its observers were ‘fear, revulsion and horror’, the urban environment turning its inhabitants into isolated savages. He associates the technology of this era (the telephone, photography) with shock, writing that later on it was film that ‘established perception in the form of shocks as a formal principle’.

On the Island, moving away from the world and the crowd, Mourant is seeking stillness, questioning whether it’s still possible to achieve it. By deconstructing the shock-inducing mechanism of cinema, he allows the viewer to observe both movement and its making. A double temporality comes into being - the narrative, made up by segments of time, and the film falling uninterruptedly. An insular time takes shape out of this ambivalence, one that allows the experience of duration without shock, granting consciousness the solid ground from where to simply perceive the flow.